The new study shows that in all permafrost regions, soil temperatures rose by an average of 0,3 degrees Celsius between 2007 and 2016. This increase in temperature was most pronounced in Siberia, where the temperature of the frozen soil rose by nearly 1 degree Celsius.

Roughly one sixth of the land areas on our planet are considered to be permafrost regions, which means the soils there have remained permanently frozen (at or below 0 degrees Celius) for at least two consecutive years. People rely on the permafrost soil as a stable foundation for houses, roads, pipelines and airports, and this is especially the case in the Arctic. Yet in the wake of global warming, the integrity of these structures is increasingly jeopardised, creating enormous costs. In addition, permafrost soils contain massive quantities of preserved plant and animal matter. If this organic material thaws along with the permafrost, microorganisms will begin breaking it down – a process that could produce enough carbon dioxide and methane emissions to potentially raise the global mean temperature by an additional 0,13 to 0,27 degrees Celsius by the year 2100.

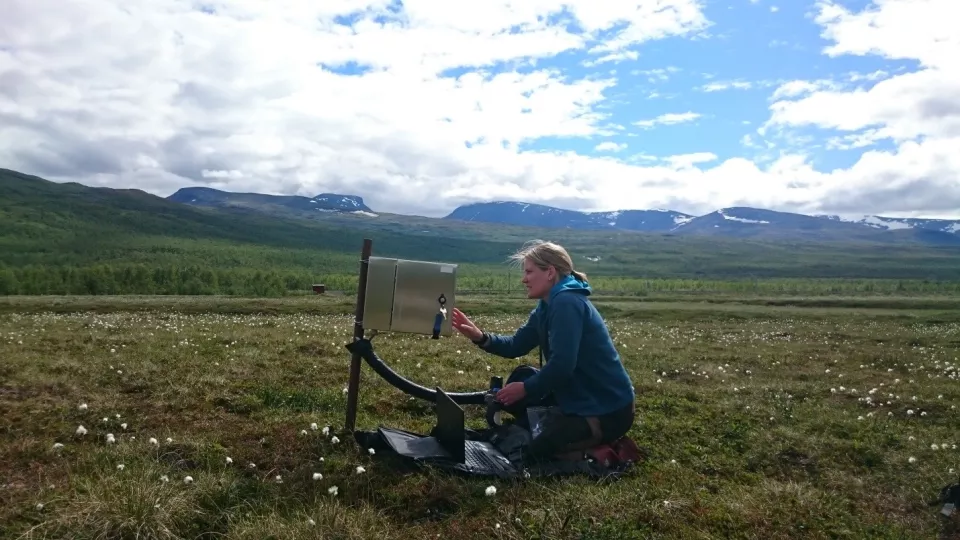

Margareta Johansson, researcher at the department, is one of the co-authors of this study, contributing with permafrost research data from Abisko, northern Sweden:

Can you say anything about the trend for the future?

- The ongoing trend of warming permafrost is very likely to continue as all future predictions are pointing in this direction. This study is the start of what hopefully will be a comprehensive long term monitoring (for many decades to come) resulting in longer time series which can provide more secure future predictions and better possibilities for local communities to adapt.

The study, released by the GTN-P (Global Terrestrial Network for Permafrost), for the first time shows the extent to which permafrost soils around the world have already warmed. For the purposes of the study, the participating researchers monitored and analysed the soil temperature in boreholes in the Arctic, Antarctic and various high mountain ranges around the world for ten years. The data was gathered at depths greater than 10 metres, so as to rule out the influence of seasonal temperature variations.

The complete dataset encompasses 154 boreholes, 123 of which allow conclusions to be drawn for an entire decade. The researchers observed the most dramatic warming in the Arctic. Significant warming can also be seen in the permafrost regions of the high mountain ranges, and in the Antarctic. The data shows that the permafrost isn’t only warming on local and regional scales, but worldwide and at almost the same pace as climate warming.

To date, the permafrost boreholes and the temperature sensors installed in them have been kept up and running by individual research groups in the context of various small-scale projects.

Read “Permafrost is warming at a global scale” online at Nature Communications.